Kicking off two weeks of weapon work at NC SYSTEMA, here’s a short article by Chief Instructor Glenn Murphy on sticks, stones, and the dangers of complacency.

Sticks and Stones

“Sticks and stones may break my bones - but words will never hurt me.”

This refrain was taught to me as a child - as it was many children of my generation. It has been around since at least Victorian times. Travel writer Alexander William Kinglake described it as an “old adage” in his book Eothen: Traces of Travel Brought Home From the East (published 1830). Doubtless, there are equivalents in other languages and cultures that date back to ancient times, or earlier.

The idea, of course, is to persuade a potential victim of childish name-calling to ignore verbal slights and provocations. To avoid responding to verbal taunts with physical violence.

This is fair enough.

After all, it’s practically never a good idea to engage in a fight over status and reputation - what author/security expert Rory Miller refers to as “The Monkey Dance”.

At best, you prevail, no-one is seriously hurt, and the taunters pick another target.

At worst, you lose (or win by injuring or killing your tormentors) - and lose your life, your freedom, or your livelihood over something you could have easily walked away from.

Knowing when to fight - and when not to fight - is a primary aspect of self-defense, and separating verbal from physical assault is critical to that decision. It’s certainly something I plan to pass on to my kids.

But there’s another, simpler lesson to be leaned from this adage. One that is encapsulated in just the first half.

That is:

Sticks and stones will break your bones.

Before finding Systema, I trained for many years in other martial systems, including karate, jujitsu, aikido, and eskrima (Filipino-style knife and stick fighting). Most of these incorporated weapon training, and empty-hand techniques versus armed attackers. Different techniques were taught against blunt-force (sticks, staves, cudgels) edged weapons (swords, knives and daggers) and firearms. For stick defense, the training approach went one of three ways:

1) real, heavy (oak or pine) sticks and staves wielded in predetermined attack patterns

2) lightweight (bamboo or rattan) sticks wielded in predetermined attack patterns 3) lightweight sticks used in free sparring, with limited contact and target areas.

After decades of this kind of work, I felt reasonably confident that I could deal with a stick-wielding attacker. Maybe not thrilled at the prospect. But comfortable with the idea, in precisely the same way that I wasn’t comfortable facing a knife.

Then in 2010, I attended a 5-day Summit of Masters / Immersion Camp with Vladimir Vasiliev and Konstantin Komarov, in a wooded camp north of Toronto, Ontario. This was my second such camp with Vlad and Konstantin, but my first with Mikhail Ryabko.

At one point - some time around day two - we were in the forest working with thick sticks and staves collected and crafted the day before. After some stick-relevant warmups and sensitivity / movement drills, Mikhail stopped the group and asked if anyone had experience with stick fighting from other martial arts. Many hands went up (although not mine, since I didn’t really consider myself an expert on this).

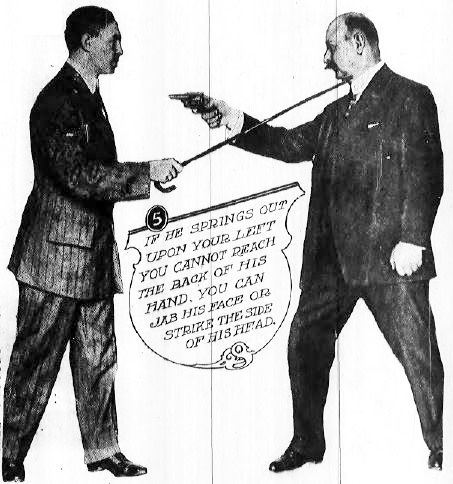

Then he asked who had ever really been hit with a stick. Again, a good number of hands stayed up (while I felt quietly relieved at my earlier decision to lay low). So Mikhail called on one brave soul, and the guy stepped forward, with his stick chambered, Filipino style. Mikhail explained that many people train with sticks as if they are harmless toys (at this point, brandishing his own short-stick with a complex, figure-eight flourish for dramatic effect). But in reality, he said, a good, honest strike with a stick can stop the fight outright. And it didn’t have to be in the head to do it.

To demonstrate this, he asked the stick-man to step forward, and hold out his armed hand. Then with a short, deft movement, he planted a heavy thwack on the guy’s bicep area. The stick dropped from his hand, and the guy’ entire structure visibly crumbled under the weight of the strike. Then (after checking the guy was okay), Mikhail asked if he could hit the body. The unfortunate participant consented.

Thwack. A sharp, heavy strike to the one pectoral muscle, and the guy not only dropped, he apparently lost the will to get up (and possibly, the will to live).

In subsequent demonstrations, with other brave volunteers, Mikhail showed that it wasn’t necessarily where you hit with the stick, but how. Sure, precision was important. And striking into tension would have the best effect. But without heaviness in the stick - a feeling that the stick had its own weight, and could find its way inside the attacker’s body after impact - you’d be wasting both your effort and your practical advantage with the weapon.

Later, I volunteered (or rather, was volunteered by my good friend Brandon Sommerfeld) to be hit with Mikhail’s mighty stick. It felt almost exactly like being punched - like a far larger, heavier object was doing the hitting. In the years since, I have taken some heavy whacks to the head, elbows and shins during stick work. None offered with malice. All good learning experiences.

But that one day back in 2010, I became convinced of two things:

1) Sticks should not be taken lightly.

By all means, practice absorption. Practice defensive movements and tactics. But make sure you understand the stakes before you go wading into a stick fight unarmed. The risk of inquiry may be higher than you think. On the other hand…

2) Most people cannot use a stick the way Mikhail Ryabko can.

Wild swings are relatively easy to avoid, and while fancy twirls and flourishes may indicate skill, fancy man will drop just as hard if your stick lands heavily and precisely.

Taken together, these two ideas suggest caution, while also offering hope. A hope that, with the right kind of training, you may still survive and prevail.

Which is exactly how you should approach armed conflict.

Glenn Murphy

Chief Instructor, NC SYSTEMA